In a striking display of strategic duality, one of America’s largest grocers is simultaneously laying the foundation for a nearly $400 million state-of-the-art distribution center in Kentucky while systematically dismantling the very high-tech, automated warehouses once heralded as the future of its e-commerce operations. This apparent contradiction is more than just a logistical shuffle; it represents a significant course correction in the grocery industry’s high-stakes battle for supply chain supremacy, prompting industry watchers to question the long-term viability of capital-intensive, robotics-first fulfillment models. The decisions being made today by Kroger could redefine the roadmap for how Americans get their groceries for the next decade.

A Tale of Two Strategies: Building the Old While Closing the New

The divergence in Kroger’s strategy is stark. The investment in the new Kentucky distribution center signals a deep commitment to the traditional retail model. This facility is designed to be a linchpin in the regional store-replenishment network, ensuring that the shelves of nearly 110 stores remain consistently stocked. In contrast, the shuttering of multiple automated Customer Fulfillment Centers (CFCs) represents a clear retreat from a strategy that aimed to bypass the store entirely for online orders. This pivot raises critical questions about the return on investment and operational efficiency of the heavily automated approach.

This isn’t just about opening one warehouse and closing another; it’s about two fundamentally different philosophies of grocery logistics colliding. One prioritizes strengthening the century-old model of stocking physical stores, a method proven by decades of operational refinement. The other was a moonshot bet on a centralized, direct-to-consumer digital future, a vision that is now being critically re-examined under the light of real-world performance data and evolving market conditions.

The High-Stakes Race for Fulfillment Dominance

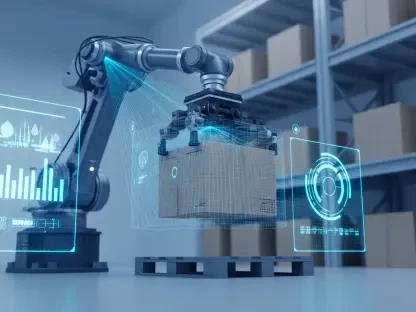

The grocery e-commerce landscape, supercharged by the pandemic, created a gold rush mentality among major retailers. The urgent need to meet unprecedented online demand fueled massive investments in automation, with the promise of robotic warehouses that could pick and pack orders with unparalleled speed and accuracy. This period was defined by a belief that technology alone could solve the complex and low-margin puzzle of online grocery fulfillment.

It was within this environment that Kroger announced its landmark partnership with UK-based tech firm Ocado in 2018. The ambitious plan was to build a nationwide network of highly automated CFCs, massive, grid-like structures where robots would fulfill online orders. This was a multi-billion dollar bet on a centralized model, positioning Kroger as a technological pioneer. The partnership was seen as a decisive move to leapfrog competitors and establish dominance in the burgeoning digital grocery market.

Now, Kroger’s strategic pivot away from the full-scale Ocado rollout is a momentous event for the entire grocery sector. As one of the earliest and most aggressive adopters of this centralized automation model, Kroger’s course correction serves as a powerful case study. Its decision to scale back suggests that the promised efficiencies may have been harder to achieve than anticipated, or that the economic model is less favorable in a post-pandemic market. This has forced competitors and industry analysts alike to re-evaluate their own long-term e-commerce strategies.

Deconstructing Kroger’s Billion-Dollar Pivot

Delving into the specifics reveals a clear strategic reallocation of capital. The new facility in Simpson County, Kentucky, is a $391 million investment in foundational logistics. Described as a modern, full-line distribution center, its primary purpose is to directly replenish the inventory of nearly 110 regional stores. Featuring scalable automation designed to enhance efficiency in the traditional supply chain, this project underscores a commitment to fortifying the core infrastructure that supports the in-person shopping experience.

Simultaneously, Kroger is decisively pulling back from its robotics-first e-commerce vision. The company has announced the closure of three of its Ocado-powered automated fulfillment centers. Further evidence of this retreat includes the cancellation of a planned CFC in North Carolina and the shuttering of a smaller “spoke” facility in Tennessee, which was designed to extend the reach of the larger centers. This rollback is not a minor adjustment but a clear and significant retreat from a capital-intensive model that was once central to its future growth narrative.

Following the Evidence from the Governor’s Office to Internal Memos

The public framing of these decisions provides critical insight into Kroger’s renewed priorities. An announcement from the Kentucky Governor’s Office celebrating the new distribution center highlighted its role in bolstering the regional economy, creating over 400 full-time jobs, and strengthening the company’s core operational infrastructure. The focus was squarely on traditional economic benefits and supply chain stability for physical stores, with little mention of direct-to-consumer e-commerce.

Internally, Kroger has justified the closure of the automated centers as the result of a “full site analysis” aimed at ensuring a “sustainable and profitable” e-commerce business. This carefully worded rationale points to a data-driven decision, suggesting that the performance, customer adoption, or financial returns of these high-tech facilities did not meet expectations. It implies a pragmatic course correction away from the original vision and toward a model with a clearer path to profitability.

Taken together, these actions paint a picture of a company engaged in a significant strategic realignment. The overarching trend is a move away from speculative, high-cost automation for e-commerce and a renewed focus on operational stability and efficiency within its established network. Kroger appears to be concluding that the most reliable path forward involves modernizing its traditional supply chain rather than attempting to replace it entirely.

Crafting a New Fulfillment Playbook: The Hybrid Model

Out of this strategic pivot, a new and more pragmatic fulfillment playbook is emerging. Kroger is shifting away from its reliance on a network of dedicated, centralized robotic warehouses as the primary engine for its e-commerce business. The new approach favors a more integrated and flexible hybrid model that capitalizes on assets the company already possesses in abundance.

The cornerstone of this evolving strategy is the leveraging of its vast physical store footprint. Instead of routing online orders to a distant warehouse, Kroger is increasingly using its local stores as micro-fulfillment centers, where employees can pick and pack orders for local delivery or pickup. This method is complemented by an increased reliance on third-party partners for last-mile delivery, creating a variable-cost network that is less capital-intensive and more adaptable to fluctuations in local demand.

The outcome is a more balanced approach to serving both in-store and online customers. This hybrid model avoids the massive upfront investment and high fixed costs associated with building and operating automated CFCs. By blending the capabilities of its existing stores with the flexibility of third-party logistics, Kroger is building a fulfillment ecosystem that appears more resilient and economically sustainable for the long term.

Kroger’s journey provided a fascinating glimpse into the trials of navigating the digital transformation of grocery retail. The company’s initial, bold foray into centralized automation with Ocado represented a major bet on a specific vision for the future, one driven by robotics and massive, dedicated facilities. However, the subsequent pivot, marked by the shuttering of some of these high-tech centers and a renewed, multi-million dollar investment in traditional distribution, demonstrated a critical lesson in adaptability. The ultimate strategy that emerged was not one of pure technological disruption but a pragmatic hybrid, blending the strengths of its extensive physical store network with the flexibility of modern logistics. This course correction suggested that for the grocery industry, the most effective path forward was not about replacing the old with the new, but about intelligently integrating them.